A 15 year-old mare presented for a 3 week history of rear-limb lameness that was associated with a "drop" of the rear fetlock joint. On presentation there was moderate swelling of the lower limb, just below the hock joint and the mare was lame at the walk. In addition, there was a 90 degree drop of the fetlock/pastern axis as noted in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1 |

The primary mechanism involved in "suspending" the fetlock joint and maintaining the proper fetlock/pastern axis is the suspensory ligament (Figure 2). The suspensory ligament originates just below the hock (red arrow) and initially is one structure (body) that travels down the back of the lower limb (yellow arrow). Approximately half way down the canon bone the suspensory ligament splits into a medial (inside) and lateral (outside) branch. The suspensory branches attach to the sesamoid bones which are located just behind and below the fetlock joint. As such, the suspensory ligament helps "suspend" the fetlock joint and a proper fetlock/pastern axis.

|

| Figure 2 |

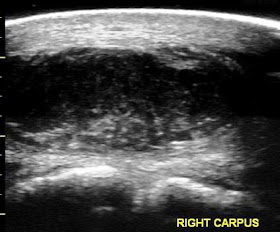

An ultrasound exam was performed to evaluate the entire suspensory ligament. The origin or proximal suspensory ligament is imaged in cross-section in Figures 3-6. The proximal suspensory ligament of the affected limb is grossly enlarged (yellow circle) and the fiber pattern is a mixed pattern with significant edema and evidence of active inflammation! There is a black and grey swirl pattern noted in the proximal suspensory ligament (tissue inside the yellow circle) of the affected limb which is indicative of severe changes.

|

| Figure 3 |

|

| Figure 4 |

When compared to the normal limb, the significant increase in the size of the proximal suspensory ligament is evident. In this case the affected suspensory ligament was 2x the "normal" size. These ultrasound findings confirm the diagnosis of proximal suspensory desmitis of the hind limb. The prognosis for this injury is poor for return to riding and guarded for return to pasture soundness. Once the fetlock has "dropped" the physical changes to the suspensory ligament CANNOT be reversed!! Treatment is aimed at slowing the progress of the condition and attempting to provide pain relief to the horse. In my experience, corrective shoeing is the MOST important aspect of managing this condition.

|

| Figure 5 |

|

| Figure 6 |

A "fish tail" bar shoe is strongly recommended for this condition. The shoe should be set extra full such that approximately 1.5 to 2 inches of shoe extended BEHIND the heel bulb. Any kind of a wedge is CONTRAINDICATED in this condition! In addition, daily treatment with ice packs over the proximal suspensory ligament followed by topical Surpass cream are indicated to reduce inflammation and provide pain relief. With corrective shoeing, adequate pain relief, and supervised turn-out, these horses may return to pasture soundness however such a condition carries a guarded prognosis.

|

| Figure 7 |