A 17 year-old gelding QH presented for a 3 week history of intermittent fever and coughing.

History:

The gelding had been treated with 3 different antibiotics over the past 3 weeks and there were no improvements in clinical signs. The problem started after the horse had been transported approximately 12 hours via truck and trailer. Within 24 hours of arriving to the show grounds the gelding was sick!

Physical exam:

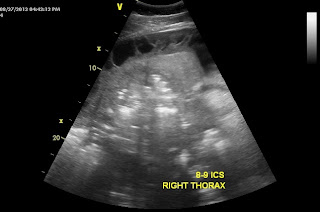

When I examined the horse, the gelding was in distress! His heart rate was 80 bpm, respiratory rate was 60-70 bpm (shallow) and his body temperature was 102 degrees. Auscultation of the thorax noted lung sounds (sound of air moving in and out of lungs) on both sides of the horse only ABOVE the level of the shoulder but lung sounds were absent or muffled below the level of the shoulder. Suspecting pleuropneumonia, I performed a trans-thoracic ultrasound exam. A significant amount of fluid was noted in the pleural space along with large fibrin tags and multiple abscesses! ( Figure 1-3).

| | | | |

| Figure 1 |

In the video clips below, the fibrin tags can be seen "floating" in the

excessive fluid within the pleural space. In addition, the fluid appears

as "cellular" suggesting a heavy component of fibrin and purulent

debris (pus).

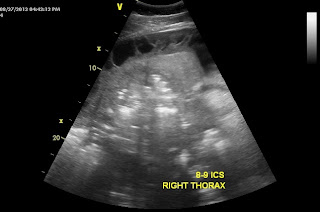

In Figure 2-3, large abscesses are noted adjacent to the body wall. Ultimately, these abscess would need to be exteriorized through a rib resection in order for the horse to completely heal. Unfortunately, the ultrasound findings combined with the severe physical distress were very poor prognostic indicators and the owner elected humane euthanasia! There was near zero chance that this horse could have been saved regardless of the medical and surgical intervention provided!

|

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

Pleuropneumonia in also called pleurisy and refers to bacterial infection of the pleural cavity and the surrounding soft tissue structures. This condition is VERY deadly and originates from bacterial colonization of the lower airway! The condition is more common in young horses that are transported long distances on a regular basis. Hence the term "shipping fever". A common belief is that horses which are transported with their head tied and a bag of hay in front of them are predisposed because they are not able to properly clear their airway of airborne debris and pathogens. Normally, horses eat with their head down which minimizes the passage of unwanted matter down their trachea and into their lungs. This condition can be treated effectively if diagnosed early, i.e, within 1-2 days of clinical signs! Aggressive medical treatment is a must and includes IV antibiotics, chest drainage/lavage, and supportive care. One of the most painful horses I witnessed as a resident was a young filly with pleurisy!! Looked like a bad case of colic but was in fact pleuropneumonia!!

.JPG)